What causes fights and quarrels among you? Don’t they come from your desires that battle within you? You desire but do not have, so you kill. You covet but you cannot get what you want, so you quarrel and fight. (James 4.1-2)

War is always in the news somewhere. Civil Wars continue in Sudan, Myanmar, Syria; frequent skirmishes are escalating in the Democratic Republic of Congo; the fighting continues between Russia and Ukraine; Israel and Hamas have been at it since 2023, and now Israel and Iran are engaged. War is a tragic human habit, and it’s so prevalent and always-on that it’s hard to keep up with all of the different battle fronts.

Saturday morning, though, an American military operation called “Military Hammer” moved war closer to the people of the United States. American forces flew into the ongoing conflict between Israel and Iran, bombing three Irani targets in an attempt. to cripple that nation’s nuclear arms programs. As I type on Monday afternoon, Iran is retaliating by bombing U.S. military bases in Qatar.

People throughout the U.S. and the world are responding very differently to President Trump’s decision and to the fact that our nation is at war. This morning’s devotional is my best go at helping us sort what the scripture and traditions of our faith say about war.

Some of you are familiar with the term “just war” — not merely war, but war conducted justly. The history and traditions that lie behind it offer us a way of sorting out the ethics of warfare -- and about this particular American attack. Hopefully this will give you a sense of how your fellow Christians (and others) have processed the moral questions surrounding war through the ages.

Throughout history, as far back as the ancient Egyptians, thinking sorts have tried to define valid reasons to go to war. One scholar summarizes the Egyptian principles this way:

"The ethics of war in ancient Egypt was founded upon three tenets of Egyptian culture...: (1) the cosmological role of Egypt, (2) the divine office of the pharaoh, and (3) the superiority of the land of Egypt and its inhabitants over all other lands and peoples." In other words, the rulers and leaders were taught that the gods had destined Egypt to a national superiority and primary role in history, partly due to the divine status of their Pharaohs.

This Egyptian ideology may not seem very ethical to most of us. It seems, for example that Vladimir Putin could claim it as his own rationale for attacking the Ukraine. But it is a considered philosophy/theology. The Greeks and Romans also entered this fray, laying a foundation on which later Christian theologians would build. Themes of the Hebrew Bible contribute too, of course, as do some verses of Christian scripture.

The Christian Tradition

When “Just War Theory” is named in our time, however, the two stars of the show have “Saint” in front of their names: the north African voice of Augustine of Hippo (4th-5th century) and, in its most enduring form, the medieval Italian theologian, Thomas Aquinas (13th century).

A traditional icon celebrating Saint Augustine of Hippo in North Africa.

Aquinas names three primary considerations that cover the reason or motivation for going to war in the first place (jus ad bellum) and the manner in which war is conducted (jus in bellum). When assessing the justness of a war effort, Aquinas names three main standards:

the war must be waged by a legitimate authority (not by guerrilla units);

it must have a just cause (e.g., to right a serious wrong, or protect valuable goods);

and it must arise out of the right intentions.

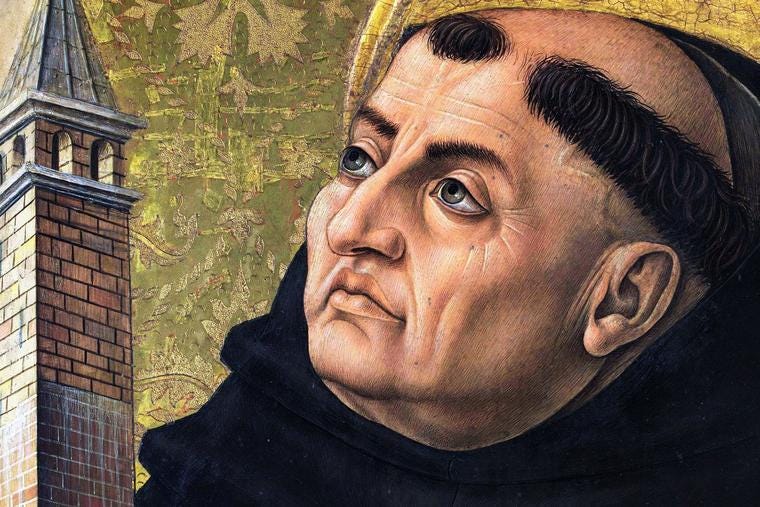

A Portrait of the Italian Saint Thomas Aquinas, painted by Carlo Crivelli in the 15th Century

As to this last requirement, the Italian doctor writes, “For the true follower of God even wars are peaceful if they are waged, not out of greed or cruelty, but for the sake of peace, to restrain evil doers and assist the good.” (Summa Theologica) Other considerations also enter for Aquinas: to be just, war must be fought...

to right serious wrongs and/or

defend against grave acts of injustice;

Additionally,

force must be necessary to redress the wrongs (last resort);

there must be a reasonable chance of success; and

the evil resulting from the use of force must not exceed the good that is intended in waging war

Aquinas’ theory has been influential in some parts of the global west, although critics have pointed to its flaws. For example, it would seem to rule out revolutionary wars, since they attack an existing “legitimate authority” (e.g., King George III) rather than being launched by one.

Notice that the economic interests of the attacking nation do not come into view. Augustine’s and Aquinas’s imagination of a just war is not defined by advantage but by justice.

Scripture and War

The Bible’s picture of war is complex. Did you notice how little space today's passage has for any upright motivations for war (Greek: POLEMOS)?

For James, wars and violenct conflict are acquisitive things: they happen when people want something someone else has and will kill to acquire it.

Jesus famously held up non-retaliation as an ideal in his Sermon on the Mount and said that “the one who lives by the sword will die by the sword”; and

the prophet Isaiah pictures an ideal future when “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.” (Isaiah 2.4)

On the other hand the Bible holds out a picture of

a God who sends Israel into battle many times with an almost Egyptian view of their rationale. “God is on our side” can be a dangerous theology, as the victims of our medieval crusades would attest.

Even the Gospels’s portrayal of Jesus seems not to be uniformly non-violent, for example, when he tells his disciples, “let the one who has no sword sell his cloak and buy one.” (Luke 22.36)

Throughout history, Christians of conscience have debated how to be “in the world but not of the world” on this issue of war. George Fox and the Quakers of the 17th century and beyond chose pacifism as their way of life and have often risked their status and risked violence from others by registering as conscientious objectors during wars.

The Quaker leader, Lucretia Mott, was an active abolitionist and a committed pacifist.

On the other hand, during World War II the German saint, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, ventured what he called “tragic moral choice”. He believed that God had outlawed intentionally killing another person, but opted for second-best morally (what he called the “penultimate”), because he could not believe that God would will Hitler's atrocities to go unchecked in the world. On this basis, Bonhoeffer even joined an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate the Fuhrer.

You see, friends, Christians have disagreed on this issue, but almost all of the conscientious conversations have stayed somewhere between radical pacifism and Aquinas’s general guidelines -- guidelines which Putin’s reasons for attacking Ukraine seem not to resemble at all. This is part of the reason why the western nations have so unanimously condemned the Russian war effort.

Our Conscience, Our Task

As we follow the news these weeks, it’s worth trying on some these varying Christian positions about war — even to look at this present American engagement through the lenses that scripture and tradition grind. Ask yourself some questions:

Is there such a thing as a just war?

Does the U.S.’s entry into the war between Iran and Israel meet just war standards of just cause and noble intentions?

Against what injustices is the attack meant to fend?

Is there no other path to peace and security?

And, more important than any of the other questions, can you imagine Jesus declaring or fighting in this war?

Christians disagree on these things. In fact, we disagree on a lot of things for good reasons. I hope this devo has mapped the moral territory in a way that helps you develop or identify your own theology of warfare.

In any case, I hope you have a peaceful Tuesday.

Prayer -- God of Iranians, Israelis, and Americans, Russians and Ukrainians, all Sudanese and Syrian and Myanmarine people — God of all people in all times, help us find ways to be neighbors on this planet without war. In the meantime, though, call your people to conscientious consideration of what your call on our lives has to do with what our nation is doing in your world, in Jesus. Amen.

Thank you, Allen, for tackling this devilish subject. Lou Ferril